Catalog

T CROW FIRE T TEE TEE YAW TEH TEH YAH

Eagle Clan Origin Myth

retold by Richard L. Dieterle

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In Radin's definitive work on the Hotcâgara, almost nothing is said about the Eagle Clan and no story of its origins is told. It is known that they had their own feast and possessed warbundles. [1] The Eagle Clan (Tcaxcep Hik'ik'áradjera) is generally recognized as the second most powerful clan next to the Thunderbirds, but the Wonághire Wâkcik Clan sometimes seems to compete for this status. [2] In one story, the Eagle Clan is said once to have held the chieftainship of the tribe. [3] Some Eagle Clan personal names are known publicly, but others are mixed in with other Bird Clan names and are difficult to verify as belonging specifically to this clan. However all names making reference to eagles are included with the understanding that at least some may be used by other clans of the Upper Moiety as well [4]:

Hitcaxcepewîga Eagle Woman

Hitcaxcepsepga Black Eagle Woman

Manixonunîka (?) Little Walker (L)

Mâxiowikerega (?) Floating Cloud (L)

Tcawaxcepsepga Black Eagle (L)

Tcaxcepsutcga Red Eagle (L)

Tcaxcep Woruxji Eagle Looking

Wîka Duck (L)

Xoracutcewîga Red Bald Eagle (D)

Xorahûka Bald Eagle Chief (L & D)

Xorap'aga Bald Eagle Head (L & D)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This short version, which is told by Oliver LaMère of the Bear Clan, is taken verbatim from the Wisconsin Archeologist:

"When the time arrived for the clans to gather at Red Banks and form a tribe, the Thunder beings whom the Creator [Earthmaker] made were to send representatives; so two of the higher class of Thunders and two of the lower class of Thunders got ready to come. Even though they were of two different clans, yet they were brothers. So they came down toward the earth (after taking human form), and as they came down it rained, not hard, but just a mist, so one of them said: "Brothers, when we get to living on the earth, the first daughter I have born to me, I will call by the name of 'Mist Woman'." As they came to earth they lighted on a branch of an oak tree. So from that and from their actions, originated their names. (The same method was used in naming all of the clans.) When they came and formed a tribe with the other clans, the eldest brother was known as the Thunder Clansman, and the second and the third brothers as the Eagle Clansmen.

The oldest brother's color was red, the second blue, the third yellow, the fourth white.

The Thunders of the oldest brother are recognized when it rains gently and the color of lightning, and the War Thunders are recognized by their fierce storms. So after a rain it is possible to hear some old Indian remark that it was such and such Thunders which went past in the rain.

Thunders are the chiefs and the Eagles are the subdivision of the chief clan." [5]

Wheat Field

From the 'Lectric Law Library's stacks

Recollections of the Peyote Road

Line

by George Morgan

[From Psychedelic Reflections, edited by L. Grinspoon and J. Bakalar,

Harvard Medical School. Copyright Human Sciences Press, 1983]

My thoughts about Peyote are closely interwoven with the religious

context of the Native American Church, the Peyote religion of the

American Indian. In my experiences with this sacred plant, Indian

Peyotists have been my companions. I am grateful to them for their

patience and understanding, and their willingness to adopt me into their

church. Peyote is considered a holy medicine among members of the

church; and it is used with the utmost respect. The teachings of Peyote

go beyond the confines of the tipi; my experiences sitting by the sacred

fireplace have helped guide my daily life. Peyote ceremonies have also

allowed me the opportunity of being closely associated with the Sioux,

who are quite remote psychically and geographically from the mainstream

of American life—far more remote than many of us realize.

Most Sioux Peyotists are full-bloods and traditionalists; their great-

grandfathers were buffalo hunters and warriors. They live in the

spacious beauty of a pine and prairie landscape, but by our economic

standards they are distressingly poor. As late as the early 1970s many

Indians in the Pine Ridge country were still using kerosene lamps. They

have retained their native language, Lakota, and their knowledge of

English is limited. Lakota is spoken throughout the Peyote ceremony. At

ceremonies someone has often interpreted in English for me, but through

the years I have come to understand much of what is said; and much

requires no words.

I attended my first Peyote ceremony in 1964. That eventful night in a

tipi at Wounded Knee was the first of many meetings and the beginning of

my acculturation to the Indian way of life. Although I was thirty-one in

1964, I was a child in the Peyote religion. The Sioux have patiently

watched me grow up in the Peyote way, and in their eyes I am now a

teenager of sixteen. They liken their religion to a school; one peyotist

has said: "You learn in here just like at school; it is graded and

becomes easier the farther along you go. " In reference to my learning,

the same man said: "It is good that you are starting now; you can always

learn more from Peyote, but you will never learn it all."

Peyotists at Pine Ridge constitute less than 2 percent of the population

(about 15,000 in 1980). The church membership is growing from within

because of an increase of children in Peyote families, but the number of

new members from outside these families is negligible. The Peyote

religion at Pine Ridge is like a large family: almost everyone knows

everyone else. Other reservations have a much higher percentage of

Peyotists: among the Navajo of the Southwest, about 50 percent. Despite

the Sioux Peyotists' small numbers, they are famous among Peyotists of

other tribes, especially for their songs. Since the Peyote religion is

pan-Indian, members often attend meetings with other tribes. At one

meeting I attended, seven tribes were represented. Thus for an Indian

visiting the reservation of a tribe not his own, the Native American

Church is a home away from home.

Although the Peyote religion is definitely Indian, it includes some

vital Christian elements. Christianity has influenced the pre-Columbian

Peyote religion since the early sixteenth century, when Spanish friars

came to the New World. Peyotists know and accept the Ten Commandments

and the teachings of Jesus; at Peyote meetings participants often recite

the Lord's Prayer, sometimes in English. Considerable time during

ceremonies is devoted to prayers. Indians are an intensely religious

people; their prayers to God and Jesus come to them easily and

naturally. My prayers are still a little awkward, although as a member

of the Native American Church I have had ample practice.

Next to the prayers, Peyote songs are the most important part of the

ceremony. As each person receives the prayer staff and musical gourd

(rattle), he holds the staff in his left hand and shakes the gourd with

his right. The drummer and other participants often sing along. These

chants, sung with compassion, create a marvelous world of sound and

meaning for Peyotists like myself, engendering visions, hope, and peace.

Some peyote songs are prayer chants which praise the name of Jesus.

Peyote is often referred to as a sacrament; it is considered a mediator

between God-Jesus and Man.

At Pine Ridge there are two contrasting ceremonial rituals and

organizations of the Native American Church: the traditional Half-moon

ritual and a more Christian version known as the Cross-fire. The Half-

moon ritual is much older and commonly occurs inter-tribally in the

United States; the Cross-fire occurs chiefly among the Sioux of South

Dakota and the Winnebago of Nebraska and Wisconsin. The leaders

(roadmen) of the Cross-fire group are bona fide ordained clergy who have

been appointed by the High Priest of the organization in the State of

South Dakota. As ordained clergy they are qualified to perform baptisms

and marriages.

In the Half-moon ceremony each participant rolls a prayer cigarette,

which is a surrogate for the peace pipe; sometimes the Bull Durham

tobacco is rolled in a corn shuck. In the Cross- fire ritual prayer

cigarettes are not used; the Bible, which is set next to the Peyote

sacrament and holy altar, replaces the smoke. At certain times during

the Cross-fire ceremony the roadman reads aloud from the Bible and

interprets readings to the congregation.

Another difference between the two fireplaces is that, at Half-moon

meetings, each participant is allowed to help himself to the sacrament

(generally four spoons of Peyote) each time it is passed clockwise

around the tipi; at Cross-fire meetings a man stands in front of the

participants and hands each of them four spoons at least the first time

the sacrament is sent around. The roadman decides how many times Peyote

should be passed around, usually three or four. It is sometimes used in

powdered form, but more often as a gravy; an infusion of Peyote tea is

also passed. Although individual members usually attend meetings

(ceremonies) with their own group, they also freely attend the other

group's meetings. Each group has its own cemetery. I like both rituals,

but I have been raised in the Half-moon and prefer it.

The Native American Church is decidedly nationalistic. Military veterans

are granted special honor. Since I am a veteran, I have the privilege of

folding the flag at ceremonies. The official colors of the church are

red, white, and blue, colors which also appear in the beadwork of

religious paraphernalia; veterans have beadwork designs of the national

flag. At almost all locations where meetings take place there is a

flagpole; the flag is raised on Veterans Day and Memorial Day and for

the funeral or memorial of a member who was a veteran. The nationalism

of the church is partly attributable to its pan-Indian organization; it

also reflects the fact that the government recognizes the Peyote

religion and allows the Indians to practice it freely. But the military

character of the Native American Church may also be a continuation of

the old warrior society, which retains high prestige among the Indians.

Women were formerly excluded from the ceremony, except for Peyote Woman,

the roadman's wife. She came into the tipi in the morning, bringing

morning food and water over which she prayed as a symbol of Mother

Earth. It was not until the 1950s that women in general started

attending Peyote ceremonies at Pine Ridge. One reason for their original

exclusion was the Indian taboo against allowing women near any medicine

during their menses. It is still considered dangerous to the health and

life of anyone taking Indian medicine, such as Peyote, to be in

proximity to a woman who is menstruating or has just given birth; thus,

women during these times respectfully stay away from meetings. Recently,

a woman who had just had a child ignored warnings and entered a Peyote

meeting; all the men at the meeting became violently ill, and many of

them vomited.

Aside from these two prohibitions, Sioux women today not only freely

attend meetings, but sit next to their spouses and sometimes even sing

Peyote songs. Indian women of other tribes also attend meetings, but

they tend to sit together, and they do not sing. Sioux women are

liberated women compared with their sisters of other tribes. Yet the

Peyote ceremony still remains a man's world; the political organization

and the ceremonial are run by men, and men predominate in numbers.

Children accompany their parents to Peyote ceremonies; the family

worship is healthy. Children begin to take medicine ritually when they

become teenagers.

There is no single reason that a person is drawn to the Peyote religion.

Some take refuge in the church as a last resort to cure a sickness after

the white man's medicine fails. Some start attending meetings out of

sheer curiosity, and some want to escape the monotony of reservation

life. Many come because they have heard that the Native American Church

is a place where one can talk to God and feel His presence. They have

heard that Peyote can change minds, habits, and lives for the better, or

that Peyote can bring happiness to man in this life. The actions, words,

and morals of Peyotists themselves have been positive living examples to

the Indian people. Another attraction is the close fellowship of Peyote

meetings.

Members of the Native American Church do not proselytize, nor do they

criticize other churches or beliefs; they prefer to live unnoticed. But

some Indians object to Peyote, the ceremony, and the people connected

with it. A few of these critics are traditionalists who follow the old

peace pipe religion of their grandfathers and see the Peyote religion as

a foreign intrusion from Mexico. The major diffusion center of the

Peyote religion was Oklahoma, and tribes such as the Kiowa and Comanche

were its major disseminators. It did not arrive at Pine Ridge until some

time between 1904 and 1912.

Some Sioux Peyotists participate in ancestral rituals with the peace

pipe, such as the vision quest and sun dance, but I know of no

traditional medicine man who has become a Peyotist. Indian alcoholics

are especially fearful and critical of Peyote. They sneeringly refer to

Peyotists as "cactus eaters. " One alcoholic told me, in a malignant

tone of voice, that Peyote was "snake juice." One reason alcoholics tend

to fear Peyote is their knowledge that Peyote conquers the alcohol in a

person's body and pushes that poison out of his system; he would thus

suffer physically and mentally through an all-night ceremony. But the

alcoholic generally refuses to admit that his recovery to sobriety and

awareness may be the beginning of a new life .

The Peyote road is the path chosen by members of the church. In the

imagery of some Peyotists, two roads diverge at a junction. The profane

road, paved and wide, with its worldly passions and temptations, is

considered to be an unholy road which leads to trouble. The alternative

is the Peyote road, a narrow unpaved path surrounded by a wilderness of

pristine beauty. All Peyotists travel this way, but each must journey

alone, for it is the road of one's own life and wisdom. In the Christian

sense, it is the road to salvation. Ethically, it is a path of sobriety

(a major step for most Indians), industry, care of the family, and

brotherly love. Its symbol is a narrow groove on top of a crescent-

shaped earthen altar that encircles the west end of the fireplace.

Rather than a straight and narrow path, it is a curved path all the way,

but the curve on the crescent altar is constant, never-varying, and so

in a sense straight. The road has not been easy for me, nor was it meant

to be. Peyotists say that up to the mid-mark of human life the Peyote

road is uphill. This is indicated by the earthen altar, which slopes up

to the center of the crescent, where the Peyote chief which is a

specially shaped Peyote plant placed on the altar by the leader of the

ceremony is set. To reach the downhill side of the Peyote chief one has

to go through (accept) Peyote, for it is considered impossible to go

around or over the sacred plant placed on top of the altar. The downhill

road symbolizes the latter half of one's life, the easier half.

Those early years of my uphill journey were difficult because of my

preoccupation with death. This morbid obsession began when I attended my

third Peyote meeting. Several people present were ill, and I feared the

spread of disease by the communal sharing of the spoon to eat Peyote and

the cup to drink Peyote tea. Two voices within me began to talk about my

death, one stressing its reality and the other constantly agreeing; the

voice-exchange continued until my awareness of death became intense. I

had been asleep to my death for thirty-one years; it now became an

intimate reality. At a meeting that I attended, a wise elderly Peyotist

said, "You can see yourself in this fireplace; you can see what kind of

man you are. If you accept what you see, you will be all right and stay

in this religion; if you don't accept what you see, you will never come

back. " More than one man attending a meeting has thought himself

attending his own funeral; he believed that he saw his own body being

brought into the tipi instead of the morning food—the church became for

him a funeral parlor. After such an experience, he may or may not want

to return to the Peyote religion. That night I arrived at the junction

and chose the Peyote road, which included the risk of sickness and the

anguish of mental torment. Yet, in the sense that "many are called, but

few are chosen," Peyotists say that "Peyote chooses you, you don't

choose it."

After that traumatic night I was aware of death every day for a period

of about 3 years. It was not an absorbing fixation, but it was a daily

reminder, my Dark Night of the Soul. I was often awakened to the image

of a black whiplash across my back and the words resounding in my ears:

"You are some day going to die." At a Peyote meeting, when I told the

members of my concern about death, one of the leaders stood up and said

that I was off to a good beginning in the Peyote way. During a meeting 3

years later I simply became aware that it was useless worrying about the

inevitable. To be uneasy is the original derivation of the word disease;

my anxiety and worry (uncertainty) about my certain death was a disease.

Perhaps there is in each of us a level where the knowledge of our own

death is so strange that it comes as a shock.

The ceremonies not only exposed me to the unknown, but allowed me an

insight into Sioux psychology and culture, which is so different from

ours in many ways. Thanks to Peyote I have become acquainted with the

genius of the Sioux mind; it has been a powerful catalyst in overcoming

ethnocentric barriers. Peyote magnified individual personalities and

cultural differences in a complementary manner, and showed what we all

had in common as human beings. During their meetings, which lasted from

12 to 15 hours, I respectfully followed the ceremonial rules of conduct—

the Indian way. The ingestion of Peyote helped us to endure the all-

night ceremony and the socializing during the following day. Alone and

decidedly outnumbered, I absorbed their culture under the aegis and

power of Peyote. Although each meeting was a culture-shock to my nervous

system, my acculturation was gradual rather than abrupt; it was a slow

blood-transfusion of cultural transformation.

After attending several Peyote ceremonies I started noticing a change in

my mannerisms. Especially noticeable was a change in my body movements

and gestures; my way of speaking and voice quality also altered. My

sense of humor and values became more recognizable among the Sioux than

among people of my own culture. Sometimes I found myself willingly

imitating the Sioux men I most admired; at other times I passively

observed those same strong personalities controlling my actions and

mannerisms. More than once during a ceremony I suddenly felt as though I

had left my body, passing into a person sitting across from me and

looking through his eyes at me. I have often wondered whether that

person simultaneously had the same experience, but Peyotists rarely

comment on their visions and appear uninterested when I tell them of

mine. They generally refrain from telling anyone what they have learned,

especially their deepest mystical experiences; they say that Peyote

teaches each person differently.

As the Peyote religion and the Sioux became more important in my life, I

began feeling more distant from my own culture, which appeared

increasingly shallow, meaningless, aggressively acquisitive, and

boastfully noisy. I was more comfortable with the Indians, who are a

quiet, refined, and soft-spoken people; their slower pace of life was

more restful to my mind, and their subtle sense of humor, especially

Peyote humor, was a joy. Indians love to joke even when the joke is on

them, but there is no scorn in their joking. Peyote humor is partly a

play on words, especially English words which are relatively new to the

Indian; they enjoy the fact that many different English words have the

same sound, and that different-sounding words have the same meaning.

At the close of a Peyote ceremony, an elderly Indian was explaining the

difference between the southern and northern Arapahoe language. He used

English words for his example: "Where the southern Arapahoe would say

'match,' the northern Arapahoe would say. . . ?" He couldn't think of

the cognate word, so a member looked up and said "lighter." Such humor

and laughter is encouraged after the ordeal of an all-night ceremony.

Often their humorous stories have a sober message; an example is the

tale of the "monkey in the fireplace," which warns against treating the

ceremony as play. The story is as follows: "No monkey business allowed

in this fireplace, but everything is in this fireplace, so the monkey

must be in there too. This engineer on the railroad had a monkey who

watched everything he did. The engineer stopped the train and went in

the depot to get a cup of coffee. When he heard the toot-toot outside,

he ran out and saw the monkey taking this train down the track. Hey,

this monkey was really having fun. He was driving the train just like a

man. He was really driving that train fast. He missed the curve and the

train went off the track, but the monkey, he jumped out of the window

and grabbed hold of a tree and was saved. He watched the train go into

the ditch."

We both laughed; then he became serious and said: "But all the people

and children on the train were killed. That's the way the monkey is: if

the man don't watch close, he will miss the curve; the monkey, he's a

monkey." Then this Indian Peyotist slowly pointed to the fireplace and

said: "That monkey will kill you if you don't watch him; no monkey

business allowed in this fireplace." Symbolically, this story indicates

that if you are careless on the curve of the Peyote road, you will fall

from the altar and burn up in the fireplace.

Through Peyote I have acquired many Indian friends and adopted

relatives. In particular, I became quite close to my adopted brother,

Silas, an Omaha-Ponca Indian who lived among the Sioux for many years.

He was a leader of the Peyote ceremony, an official of the church, and a

man of great charm and spiritual power. He was about 20 years older than

I, a wiser brother. Together, we spent much time visiting and attending

Peyote meetings. He had been raised in the Peyote tradition, and he

taught me much about that tradition and about the good life. For

instance, he taught me the need for humility before entering the tipi to

pray. To attend a meeting with a know-it-all attitude, that of a "big

shot," will usually cause suffering throughout the night. He said: "Over

there are some tall weeds that are now bent by the cold. That's what

Peyote can do to a man who thinks he knows everything. Peyote will bend

him down and turn him inside out. " I have seen that happen since and I

know that his analogy was accurate.

Because of his vast experience and clear, quick mind, he was always

several steps ahead of me. I shall never forget that when I told him I

thought Peyote was good, his answer was: "You say that Peyote is good;

what's good about it?" No one has satisfactorily answered his question.

Once when Silas had a ruptured hernia, a few Peyote boys helped him

through to health. They prayed, drummed, and sang through the night, and

they spoon-fed Silas about 150 Peyote. He was well by morning; the

ambulance returned to the hospital without him.

Silas told me of his vision when he ate that large amount of Peyote:

"Brother George, I had so much Peyote in me that when I raised up from

the bed the Peyote would come up my throat to my mouth. While the boys

were drumming and singing I suddenly got out of bed opened the door and

went outside; a short distance from the house was a large hill. I walked

to the hill and saw a shiny new ladder going all the way to the top. I

climbed the ladder to the top of the hill. I looked around, everything

up there was so beautiful. The air was clean and fresh; there were all

kinds of pretty colored flowers. When I looked back to the ladder it was

old and broken; many rungs were missing. Since I had no way of getting

back down, I decided to enjoy where I was; later I looked back at the

ladder and it was once again a shiny new ladder. I finally climbed down

the ladder and walked back to the house. The people in the house looked

very sad. I walked up to the bed and looked down at the man lying on the

bed; he had his eyes closed and looked rested. I saw that the man on the

bed was myself. I then lay down to rest. When I awoke my sickness was

gone. The large hill was a hill of Peyote, all those Peyote represented

my sins. The top of the hill was paradise." Although Silas often ate

large amounts of Peyote, he told me that if a person is in the right

spirit "just a taste of Peyote on the tip of your tongue is enough. "

At meetings, Silas was a strict disciplinarian. At a house meeting in

winter I fell unconscious from the lack of oxygen. The one-room log

house was sealed airtight; it was crowded and stuffy. There was no air

circulation; the fireman had brought in a large pan filled with live

coals which further heated an already hot room. Silas was sitting next

to me. When I fell unconscious, I dropped my pheasant-feathered fan on

the floor. I was revived about 10 minutes later. The first thing Silas

said to me was, "Pick up your fan!" A few minutes later I told Silas

that I believed the reason for my passing out was that the live coals

were eating up the oxygen. He agreed, but nothing was done about it.

Under the influence of Peyote, the loss of consciousness was especially

meaningful. I felt as though I had died; the darkness of unconsciousness

came before I realized what was about to happen. I wondered whether

death would be like that, quicker than conscious thought. A tall, quiet

Arapahoe man revived me; I saw him clearly before I could hear any

sound, and it was about a minute before I could hear. I went outside in

the bitter cold to get some fresh air. The Arapahoe man walked up to me

and said: "You are doing all right in this Peyote way, but don't be in a

hurry; take your time. " Several days later, a leader in the Peyote

religion who had heard about my fainting said: "I heard that Peyote

finally caught up with you."

I write of Silas in the past tense because he died in 1973. Visiting his

blood relations, the Omahas of eastern Nebraska, is the closest I can

come to being with him. In their eyes I am a welcomed relative who has

come home. Whenever I attend a Peyote meeting, especially among his own

people, he is close to me. Although all tribes have essentially the same

Peyote ritual, there are variations which are highly important in the

minds of the Indians. Each tribe has its language and culture; each has

its own style; each has its own genius. At my first birthday meeting

among the Omahas, I said that since I was familiar with the Sioux way,

they could continue singing while I prayed with a prayer cigarette

during the main smoke. The Omahas looked startled; the air seemed

electrified by the cultural transgression. After a silence which seemed

to last an eternity, Henry, the leader and my adopted nephew through

Silas, said: "Uncle George, we will pick up these instruments (musical

instruments) again when you are finished with your prayer; that's the

way we do it here, so that's the way it is going to be, Uncle George."

Although I continued to live and work within my own culture, my heart,

spirit, and mind resided with the Peyote religion and the Indians. Thus,

I lived in two worlds—physically among my own people, emotionally among

the Indians. Living within an hour's drive from the reservation allowed

me easy access to the source of my emotional life. Because of the

increasing ease and frequency with which I went back and forth, my image

of the reservation's entrance and exit was that of a swinging door. As I

felt an increasing need to be on the reservation, I began attending more

meetings and visiting more often. All of us Peyotists needed emotional

support as an integral part of group solidarity and the fellowship of a

community of seekers. The social group using Peyote became as important

to me as the plant and its powers. Whatever their age, Peyotists are

endearingly called " Peyote boys . " They are a brotherhood of seekers

who are youthful in spirit and attitudes, in their curiosity and

willingness to learn.

As my cultural metamorphosis became less detectable to myself, it became

more obvious among friends and relatives of my own culture. Yet I could

never become fully Indian. A Peyotist made this clear to me by saying:

"This way helps us to become more Indian and it helps you to be more

like George Morgan. " At first Peyote enabled me to see the Indians as I

wanted to see them: in an idealizing light. But eventually I learned

from Peyote that their culture had its own snags and contradictions, and

my view became more balanced. In time, Peyote aided me in understanding

and respecting my own culture. For instance, Indians have a sharing

culture; we do not. Peyote helped me to understand the advantages and

pitfalls of sharing. Of course, any discerning mind might in time come

to the same understandings; one does become wiser with age. With Peyote

too it takes time to learn about life and cultural differences; wisdom

cannot be hurried .

By reconciling the opposed cultural values in my mind, I diminished

their hypnotic influence and escaped the clutching grip of ethnicity. An

identity crisis ended: the tenuous swinging door vanished; I stepped out

of both cultures and took a deep breath of fresh air in a cultural void.

I could now enjoy both cultures, and I could move freely and safely

through them. To arrive at this point along the Peyote road took me

years of relentless effort .

The Peyote religion also advanced my formal education. One morning as I

sat by the sacred fireplace I felt an urgent desire to journey to the

land where Peyote grows and study the plant's environment and trade

channels. That impulse was prompted by substantial price increases for

the plant and occasional supply shortages which troubled the Indians. My

university training in geography and plant ecology had prepared me to

study the biogeography and economic history of Peyote. As there was a

gap in the literature, I decided that this study would become my

doctoral dissertation, and I felt that the knowledge gained from it

would help Peyotists to secure a dependable supply in the future. I

spent several months over a period of 2 years in the Texas brush country

studying Peyote. I learned about the plant's life cycle, habitat, growth

rates, and geographic range past and present. I also studied the history

of Peyote trade between the Peyoteros (a group of Spanish-American

Peyote traders) and the Indians.

I sincerely believe that Peyote guided me in this study, for I met no

obstacles in seeking information about a delicate and somewhat secretive

subject. I also believe that Peyote protected me from harm in the

rattlesnake-infested thorn brushes. The details of my study are too

complicated to relate here, but the thesis is of value in understanding

the present problems of Peyote supply and how they arose. If Indians

make the effort, as they surely will, there should be a dependable

supply for their needs in the future. In a strange way I feel as if

Peyote selected me to do that study, for other Peyotists with artistic

talent have been inspired through Peyote to paint religious paintings

connected with the ceremony; others have done beautiful beadwork.

I would not casually suggest to anyone that he attend a Peyote ceremony.

It is difficult to sit through an all-night ceremony. And Peyote is not

easy to swallow: it is extremely bitter, even to experienced Peyotists,

and occasionally nauseating, especially for beginners. A person of

sincere intent would be welcome: it is a church. He would find

hospitality: Peyotists are courteous and respectful. But it is well to

remember that Peyote is not a plaything; Peyotists say that "if you play

around with Peyote, it will turn around and start playing with you."

The Native American Church is not for the curiosity seeker: it is a

serious religion.

The Peyote road has shown me many wonders, and I believe it is the same

for other Peyotists. I shall continue to follow that adventurous path,

that sublime way of life.

-----

From material contributed to the Library by Tom Leonard, a member and

director of the Ponca Chapter of the Native American Church of Oklahoma.

Italian River

1957 - 1958 5th "Judy" Wilma Louise Collins

v 1958 - 1959 6th Sharon Goodluck-Eluska

v 1959 - 1960 7th Marylene Blueeyes Young

MISS NAVAJO

The Nobel Peace Prize 1988 was awarded to United Nations Peacekeeping Forces. operations. In 1996 The Medal Committee of the Norwegian Defense Ministry approved the medal as an official Norwegian/International medal. This International Peace Prize Medal is an award of Norway and is available to Korea Defense Veterans. A reproduction of the Nobel Diploma and a personal certificate are authorized by the Norwegian Defense Ministry and the UN to be given with the medal.

Medal specifications:

- The medal is made of gold gilt metal with enamel in light blue and white colors. The full size medal has a diameter of 35 mm, and the Mini Medal has a diameter of 20 mm.

- The ribbon is light blue with the Norwegian flag colors as vertical stripes in the center (red, white and blue).

- The obverse/front of the medallion shows the UN globe surrounded by a wreath on a light blue enamel background.

- The reverse side is light blue enamel and has a curved gilt text reading: “Friendship Across the Frontiers” and UN in white enamel.

- Bar at top of ribbon with light blue enamel background and gold text reading: “The Nobel Peace Prize – 1988”.

The following UN missions qualify:

- UN Truce Supervision Organization - from 1948

- UN Military Observer Group India Pakistan - from 1949

- THE KOREAN WAR - from 1950 to 1953 - one of the first missions under UN

COMMAND

- KOREA MISSIONS - missions under UN COMMAND from 1954 - 1988

- UN Emergency Force - from 1956

- Operation des Nations Units au Congo - from 1960

- UN Yemen Observer Mission - from 1963

- UN Force In CYPRUS - from 1964

- UN Emergency Force II - from 1973

- UN Disengagement Observer Force - from 1974

- UN Interim Force In Lebanon - from 1978

- UN Iran/Iraq Military Observer Group - from 1988

Documentation Required:

The International Peace Prize Medal 1988, requires documentation to demonstrate UN Mission participation or Korean service prior to December 10, 1988. This proof of participation can be copies of military documents, certificates, orders, etc or certification by a U.S./Korea or other veterans organization. The KDVA will certify service for its members if requested. Note, this is not an official United Nations award and is not the equivalent or replacement for the UN medal that the KDVA is petitioning the UN to award for cease-fire service.

Order Information:

To order the medal you must provide documentation that you served in Korea between 1950 and 1988. The medal price will fluctuate as the value of money changes but the full medal, mini medal, ribbon package will cost around $165.00 and 170.00. Payment can be a transfer of funds electronically or by credit card. Your credit card will be charged a fee of 3 percent of the total. It is important to note that U.S. dollars are converted to Euro dollars and then to Danish currency. The medal is priced in Euro's but the company handling the orders is in Denmark. Download the order form and follow the instructions. (Order Form Here)

Descendancy Chart of Thomas Francklyne

Thomas FRANCKLYNE, b. 1537

+-- Robert FRANCKLYNE, b. 09 Apr 1563

+-- John FRANCKLYNE, b. 15 May 1567

+-- James FRANCKLYNE, b. 09 May 1570

+-- Henry FRANKLIN, b. 26 May 1573, d. 25 Oct 1631

+Agnes JAMES, m. 30 Oct 1593

+-- Benjamin Thomas FRANKLIN, b. 08 Oct 1598, d. 1681

+Jane WHITE

+-- Thomas FRANKLIN, b. 11 Apr 1637, d. 06 Jan 1702

+-- Samuel FRANKLIN, b. 17 Nov 1641

+-- John FRANKLIN, b. 20 Feb 1643

¦ +Ann JOPH

+-- Joseph FRANKLIN, b. Oct 1646

¦ +Sawah PAVYER

+-- Benjamin FRANKLIN, b. 23 Mar 1650, d. 1728

¦ +Hannah WELLS

+-- Josiah FRANKLIN (Benjamin Franklin's Father), b. 23 Dec 1657, d. 1745

+Ann CHILD, d. circa 1689

+-- Elizabeth FRANKLIN, b. 02 Mar 1677

+-- Samuel FRANKLIN, b. 16 Mar 1681

+-- Hannah FRANKLIN, b. 25 May 1683

+-- Josiah FRANKLIN, b. 23 Aug 1685

+-- Joseph FRANKLIN, b. 06 Feb 1687

+-- Joseph FRANKLIN, b. 30 Jun 1689

+Abiah FOLGER (Benjamin Franklin's Mother)

+-- John FRANKLIN, b. 07 Dec 1690 Boston, Suffolk Co., Massachusetts, 20 Jan 1756

¦ +Mary GOOCH

¦ +-- John FRANKLIN, b. 1750 Boston, Suffolk Co., Massachusetts

+-- Peter FRANKLIN, b. 22 Nov 1692 Boston, Suffolk Co., Massachusetts, d. 01 Jul 1766

¦ +Mary HARMAN

+-- Mary FRANKLIN, b. 26 Nov 1694, d. 1731

¦ +Robert HOLMES, m. 03 Apr 1716

+-- James FRANKLIN, b. 04 Feb 1696 Boston, Suffolk Co., Massachusetts, d. 04 Feb 1735

+-- Sarah FRANKLIN, b. 09 Jul 1697 Boston, Suffolk Co., Massachusetts, d. 23 May 1731

¦ +James DAVENPORT

+-- Ebenezer FRANKLIN, b. 20 Sep 1701 Boston, Suffolk Co., Massachusetts, d. 05 Feb 1702

+-- Thomas FRANKLIN, b. 07 Dec 1703

+-- Benjamin FRANKLIN, b. 06 Jan 1706 Boston, Suffolk Co., Massachusetts, d. 06 Apr 1790

¦ +Deborah REED, m. 01 Sep 1730

+-- Lydia FRANKLIN, b. 03 Aug 1708 Boston, Suffolk Co., Massachusetts

¦ +Robert SCOTT, m. 1731

+-- Jane FRANKLIN, b. 27 Mar 1712 Boston, Suffolk Co., Massachusetts

Table of Contents

CD II

Part I: Ioway ~ Otoe-Missouria Alphabet

Ten Commandments- - - 1

Part II:

Miscellaneous Sentences- - - 2

Part III: Church Hymns

Hinyíno Jesus Nahúnwidawina- - - 5

Náwe Waháminana- - - 5

Wakándeyiße Áwino- - - 5

Part III: "A Short Prayer to Memorize"- - - 6

Part V:

Miscellaneous Sentences- - - 7

Part VI:

Reminiscences of Grandmother- - - 14

Hinyíno Jesus (Church Hymn)- - - 15

Part VII: Being A Present Day (1970s) Ioway- - - 16

Biographies of the Elders- - - 20

Table of Contents

CD I

Part I: Ioway ~ Otoe-Missouria Alphabet

Vowels- - - 1

Consonants- - - 2

Glottal Stops; Nasal Vowels; Consonant Combinations- - - 5

Animals and Birds- - - 7

Turtle Song- - - 8

Hunting Song- - - 8

Part II: Conversational Phrases

Getting Acquainted; Greetings; Scenery- - - 9

Conversational Dialogues- - - 10

Narratives

Náwo Núwe (Two Roads)- - - 13

Wakándeyiße (Church Hymn)- - - 14

Dagúre Ha^unna je (Whatever am I going to do?)- - - 14

Jesus Hanäh^éxwe Howana (Church Hymn)- - - 14

Hináge Ñík^eda (Woman at the Well)- - - 15

Jesus Mínke Rígragina (Church Hymn)- - - 15

Miscellaneous Words & Sentences- - - 16

*******

TO ORDER

Send Money Order To:

Báxoje-Jiwére Language Project

Jimm G. GoodTracks

P.O.Box. 267

Lawrence, KS 66044-0267

Email Jimm GoodTracks

____________________________

Ioway-Otoe-Missouria

Nations Language Books

(out of print - limited stock)

IOWAY - OTOE - MISSOURIA NATIONS'

LANGUAGE STUDY BOOKS I & II

Beginner and Intermediate

Provides the basis for a primary and intermediate level language study. This includes the Ioway-Otoe alphabet, vocabulary, word formation, verb conjugation, sentence structure and interactive dialogues. $15.00 per book

Include $4.00 per each book for Packaging and Postage.

With selected art work by Otoe-Missouria

and Iowa Indian children of Red Rock School.

Also

A 1985-86 Community Calendar with

Ioway-Otoe terms for every month and

RARE FAMILY PHOTOGRAPHS

OF IOWAY - OTOE - MISSOURIA ELDERS

And HISTORICAL INFORMATION EVENTS on each month

$7.50 per issue

Postage is already included

To Order, Send Money Order to:

Baxoje-Jiwere Language Project

Jimm G. GoodTracks

P. O. Box 267

Lawrence, KS 66044-0267

Email Jimm GoodTracks

The first example is indage' ouai panis, glossed as 'je suis indigne de vivre, je ne me'rite plus de porter le doux nom de pe're'. The second is tikalabe', houe' ni que', glossed as 'c'est a' dire, nous te croyons, tu as raison'. These can be interpreted representing as a Siouan language in the following fashion.

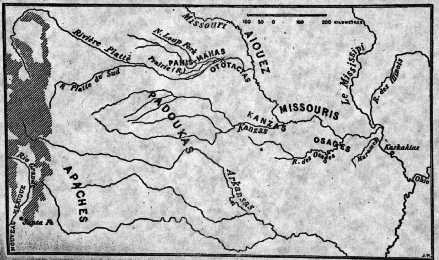

The Missouri were an aboriginal tribe that inhabited parts of the midwestern United States before the American settlers arrived. The tribe belonged to the Chiwere division of the Siouan linguistic family, with the Iowa and Oto. The tribe lived near the mouth of the Grand River in Missouri, the mouth of the Missouri River, and a place called The Pinnacles in Saline County, Missouri.

Their name means the people who build long canoes. It is an Illiniwek word. In their own language, the Missouri call themselves Niúachi. There were known as the Waçux¢a by the Osage and Wa-ju'-xd¢иг, by the Quapaw.

According to the enthnographer James Mooney, the population of the tribe was about 200 families in 1702; 1000 persons in 1780; 300 in 1805; 80 in 1829, when they were living with the Oto; and 13 in 1910; afterwards not separated from the Oto.

Their name has been lent to the state of Missouri and the Missouri River.

Truman Black, a full-blooded Otoe Indian, tries to recall the Otoe word for “mama” while discussing tribal culture and language yesterday at Van Meter State Park. “If you don’t speak it, you lose it,” Black said.

MIAMI, Mo. - After taking a sip of water, Truman Black placed the tips of his fingers against his chest and closed his eyes. He swayed slightly as he sang a soft, deeply powerful melody.

"The Flag Song," as Black called it, honors Otoe predecessors who fought for their culture at home as well as for the United States abroad.

"Our tribe, many a tribe, have great honor in their warriors," said Black, who calls himself one of the last full-blooded Otoe American Indians.

Black, 68, of Oklahoma City, spoke about the Otoes’ history, language and culture yesterday at Van Meter State Park, some 75 miles west of Columbia. About a dozen people came to the event, which was sponsored by the Missouri Department of Natural Resources.

The Otoes originated in what is now the Upper Midwest in the 1300s or 1400s. They moved west in the 1500s to 1600s before settling in the 1750s with the Missouri and Ioway American Indians in what are now Nebraska and Iowa.

Connie Winfrey, historical site administrator for Van Meter State Park, said that after the Missouri, Ioway and Otoe tribes migrated from the Great Lakes, the Missouri Indians stayed near the Missouri River in what is now Saline County, and the Otoes went up the river to Nebraska.

In the late 1700s, when the Sauk and Fox tribes defeated the Missouri Indians, they went up the river and joined the Otoes.

"When Lewis and Clark came through here, the Missouri Indians weren’t living here. They found them with the Otoe," Winfrey said. "The Missouri Indians and the Otoe were the first tribes Lewis and Clark encountered on their trek west."

Black said the Missouri, Ioway and Otoes share similar languages. The Ioway language, he said, has only a handful of words with meanings that differ from the Otoe language. The Missouri Indians spoke the same language but at a quicker pace, he said.

"If we got the people to slow down enough, we could understand them," Black said.

At its peak, Black said, the Otoe tribe had about 2,300 members. Today, he said, there are a little more than a dozen "full-blooded" Otoes.

Language is the key to the preservation of culture, Black said. "You lose your language, you lose your culture," he said.

Black said that because the Otoes do not have a written language, he learned the tribe’s customs and language from Arthur Lightfoot, an uncle of Ioway and Otoe descent. Black said he is among only a handful of people who know how to speak the language.

Black said descendants of the Otoe tribe don’t know American Indian history because their parents no longer talk about it. "They are no longer told stories as I was when I was growing up," he said.

During a question-and-answer session, Black explained how to say the word "daughter" in Otoe but struggled to recall the word for "mama." "If you don’t speak it, you lose it," he said.

Black also discussed his confrontations with bigotry. He told how he was refused service in 1957 at a Ponca City, Okla., bar while wearing his Navy uniform. The server told him that because he was an American Indian, he could not buy beer.

Black said he once was confined to a segregated portion of a cafe.But he said he’s never been ashamed of his heritage. "I have never had a reason not to be prideful of my heritage."

He said that it was emotional remembering his past because many of the people who know the Otoe culture are dying off.

"I’m of an age where I knew the elders that lived the culture, still spoke the language and were still in the cultural customs of our Indian history," he said. "There are many people of my age today who don’t have that spiritual feeling that I have because of knowing of the language and the customs."

Dubble Bubble was invented by an accountant named Walter Diemer in 1928. Accountants are awesome!

Truman Washington Daily

1898-1996

Truman W. Daily was born on October 9th, 1898 in the Oklahoma Territory. Eighteen years earlier, his tribe, the Otoe-Missouria, had left their origins of Nebraska and receded southward to Red Rock. His parents were George Dailey who was Missouria and Otoe, and Katie Samuels, who was Ioway and Otoe. He was known by his Eagle Clan name, Mashi Manyi “Soaring High”, and Sunge Hka, “White Horse”.

Truman was a member of a group called the Eagle Clan, which took the responsibilities of war. They served as warriors, but their main purpose was to uphold peace and prosperity. They planned war strategies, but their fighting was always done on the defensive, not the offensive.

Truman married Lavina Koshiway on March 17th, 1928. After marriage, they went on to serve in the Native American Church, working to keep the traditional Otoe Missouria customs alive. Truman had great respect for the tradition of his peoples, which he learned from his father, who belonged to a group called the Coyote Band. They believed in remaining true to the traditions that their forefathers had used. He believed in the use of the traditional ceremonies so they would not be lost. He was the last to know the reasoning behind much of the traditional ceremonies and rituals used.

In the 1970’s, Truman taught the Otoe Missouria language in tribal classes. It was said that he was a great teacher, and he utilized many great characteristics of himself and brought that upon to his students. He may have been the last surviving speaker of the Otoe-Missouria language, but at his time of death there were many people who had been influenced by his teachings. Truman also worked for Disneyland as the master of ceremonies for the Native American Indian Cultural Center.

Truman attended The University of Oklahoma Columbia and received his PhD in humanities. In 1988 he volunteered for Louanna Furbee at the University of Missouri as a language consultant. She was doing a project to document the Otoe-Missouria language, before it was lost forever. Truman died on December 16th, 1996, at the age of 98. At the time of death, he was the last surviving speaker of the Otoe-Missouria language. Strangely enough, he was not given a traditional Otoe-Missouria ceremonial funeral.

REFERENCES

1) Ioway Cultural Institute." Truman W Daily (1898-1996) IN MEMORIAM http://ioway.nativeweb.org

2) Brokenclaw.com." Photographs http://www.brokenclaw.com/genealogy/photo.html

3) The Menomineeclans Story." The Eagle Clan http://www.library.uwsp.edu/menomineeclans/eagleclan.htm

Written by Emmy Baskerville, 2003